4th Sunday in Ordinary Time [A]

February 1, 2026

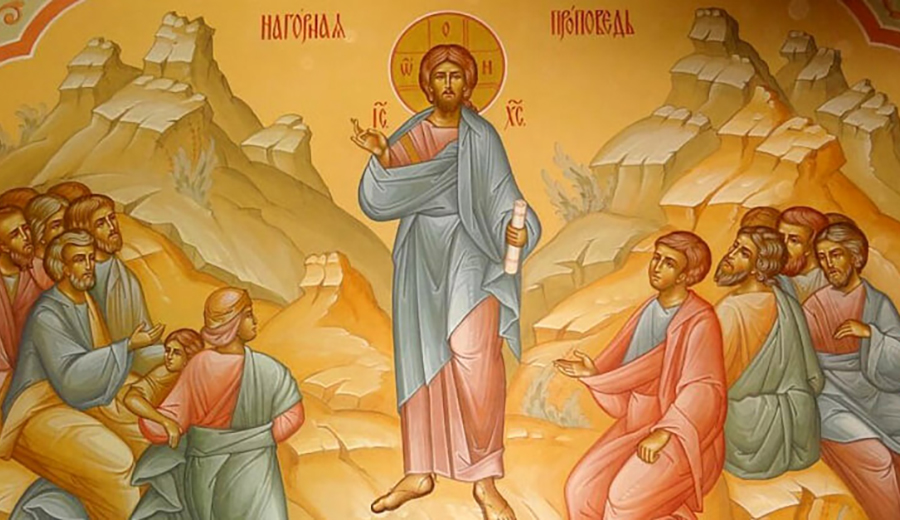

Matthew 5:1-12a

Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount begins with the Eight Beatitudes. Pope St. John Paul II calls the Beatitudes the “Magna Charta of Christianity,” comparing them to the Ten Commandments of the Old Testament. He notes, “They are not a list of prohibitions, but an invitation to a new and fascinating life.” They are indeed an exciting invitation because they address the one fundamental desire we all share: happiness. However, as we read the Beatitudes, we realize that Jesus’ path to happiness is counter intuitive. Why is this?

We tend to believe that possessing wealth is a sign of God’s blessing and the means to our happiness. Yet, Jesus teaches, “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven.” While Jesus speaks specifically of “poverty of spirit,” our eagerness to achieve major successes, accumulate wealth, and stay at the top often leads to health problems, mental exhaustion, and difficult relationships with our loved ones. Eventually, these pursuits wear down our spirits, and we find we are not truly happy.

We often think that laughter and “good vibes” are the surest signs of happiness, but Jesus says that the one who mourns will be comforted. Sometimes, we forget how to mourn when we lose something precious, such as a loved one. Instead, we try to run from grief by indulging in instant pleasures or endless scrolling, distracting ourselves with busy activities and overworking, or even blaming God. Yet, mourning helps us confront the truth of our fragile nature, rely more on God’s mercy, and ultimately find healing and comfort.

We normally perceive that through strength, aggression, and dominance, we can acquire whatever we desire. Jesus teaches exactly the opposite: the meek will inherit the land, the merciful will receive mercy, and the peacemakers will be called children of God. While this sounds counter-intuitive, when we look around, we realize that so many problems in our families, societies, and environments are caused by human greed, violent aggression, and vengeance. Only when we learn to be gentle, merciful, and peace-loving do we create peace not only within ourselves but also for the people around us.

Often, we unconsciously fill our hearts with ambitions to be the greatest, most powerful, and influential. We allow desires for pleasure and instant gratification to control us, but Jesus reminds us that only the pure in heart can see God. Hence, it is critical to be aware of what contaminates our hearts, to acknowledge these impurities, and to ask for God’s grace to purify them. In the Catholic tradition, this process is the examination of conscience and the confession of sins, through which God’s grace cleanses our hearts and reunites us with Him, the source of our happiness.

Finally, Jesus concludes the Beatitudes by positioning Himself as the endpoint of our happiness. Jesus is not just a wandering wise teacher promoting self-help principles for successful living, but the source of happiness itself. Unless we cling to Him and offer up our hearts to Him, our lives remain fruitless, and eternal happiness remains beyond our reach.

Rome

Valentinus Bayuhadi Ruseno, OP

Guide questions:

Which worldly ambition/s is currently draining my energy, and how might letting go of it bring me more peace? When I feel hurt or overwhelmed, do I tend to numb the pain with distractions (like screens, busy work, or pleasure), or do I bring that grief honestly to God? Is there a conflict in my life where I am trying to “win” through dominance or aggression, rather than resolving it through gentleness and mercy? If I look at my daily habits, do they show that I am seeking happiness primarily in worldly achievements, or in a relationship with Jesus?