1st Sunday of Lent [A]

February 22, 2026

Genesis 2:7-9, 3:1-7

Traditionally, the Gospel reading for the first Sunday of Lent is the story of Jesus in the wilderness for forty days, where He fasted and was tempted by Satan. However, in this reflection, we will look deeper into the first reading from the Book of Genesis.

The Church combines two stories in this first reading: the creation of Adam (Gen 2:7-9) and the fall of our first parents (Gen 3:1-7). In order to do this, the lectionary skips around 16 verses (Gen 2:10-25), omitting Adam’s activities in the Garden of Eden and the creation of Eve. I believe the reason is not purely practical (simply avoiding overly long reading), but rather that the Church wishes to show us a hidden truth that connects the two stories.

First, we must recognize that the story of the creation of Adam is not merely a biological lesson, but a profound theological truth. Adam was created from the dust of the ground (עפר מן־האדמה – apar min ha-adama). We, as humans, are nothing but mere soil—fragile, dirty, and essentially worthless. In fact, there is a clear play on words in Hebrew to remind us of our lowly origin: the word Adam (the first man) is almost identical to the word for ground (Adama).

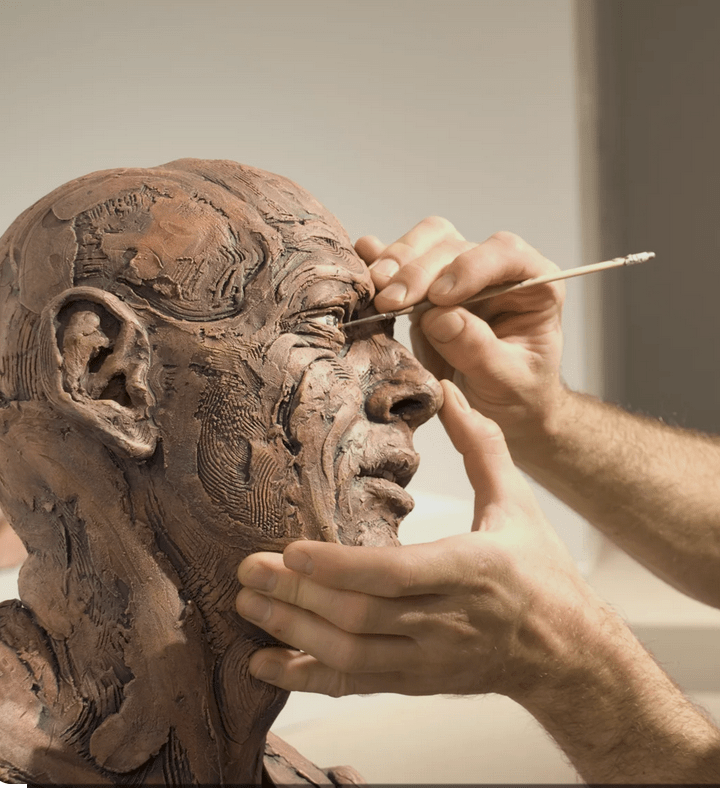

However, the Book of Genesis pushes further by pointing out that while we are nothing, God is everything; while we are powerless, God is omnipotent. Yet, despite the infinite gap between God and us, the author of Genesis reveals God’s immense love for humanity. Depicted as a divine artisan with His skillful hands and life-giving breath, God formed this worthless dust into one of His most refined creatures. Furthermore, God made us His co-workers in His Garden, entrusting us to care for the other creatures. We are who we are solely because of God’s love.

Moving to chapter 3, the serpent tempts Adam and Eve. His strategy is simple yet extremely effective. He claimed that God was not telling the truth and that God did not want Adam and Eve to be like Him, thus forbidding them to eat the fruit. The idea of being like God was extremely attractive, and pride began to corrupt their hearts. They desired to be like God without God, acting as His rivals rather than living as His servants. They forgot the most fundamental truth about themselves: they are nothing but dust, and everything good they have comes from God. Consequently, they fell.

By joining the stories of Adam’s creation and his fall, the Church teaches us that when pride poisons our hearts, we begin to ignore our humble origins and are doomed to fall. As St. John Chrysostom stated in a 4th-century homily: “[the story of Adam’s creation] is to teach us a lesson in humility, to suppress all pride, and to convince us of our own lowliness. For when we consider the origin of our nature, even if we should soar to the heavens in our achievements, we have a sufficient cause for humility in remembering that our first origin was from the earth.”

Rome

Valentinus Bayuhadi Ruseno, OP

Guide questions:

In what areas of my life do I forget my humble origins (“dust”) and fail to recognize that all my gifts, talents, and successes ultimately come from God? How does pride manifest in my daily choices? Do I sometimes try to be “like God without God” by seeking total control over my life, rather than trusting Him as His servant and co-worker? When I “soar to the heavens” in my earthly achievements, what practical practices can I adopt to stay grounded and remember my fundamental reliance on God’s love?