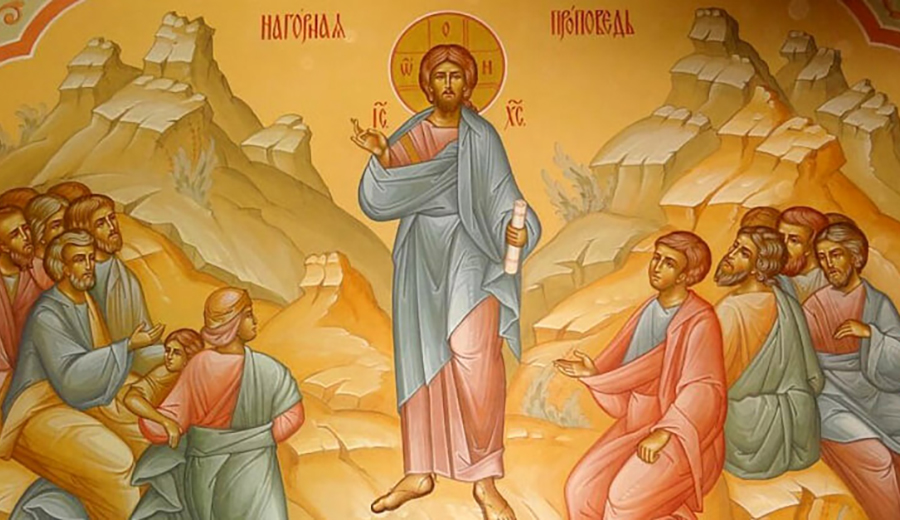

5th Sunday in Ordinary Time [A]

February 8, 2026

Matthew 5:13-16

Continuing His Sermon on the Mount, Jesus reveals our identity as the “light of the world.” As such, our light must shine and be seen by others. Interestingly, only one chapter after this teaching, Jesus instructs His listeners: “Be careful not to practice your righteousness in front of others to be seen by them” (Mt 6:1). At first glance, it may seem that Jesus is contradicting Himself. How are we to understand this?

While these instructions appear opposing, they are, in essence, complementary. The bridge between these two statements is intention: is the action meant to glorify the Lord or simply to seek personal glory? As Matthew 5:16 suggests, the motivation behind our good works is decisive. If we perform noble deeds to receive personal recognition, they lose their merit before the Lord. However, if we sincerely desire to lead people to God, our efforts truly please Him rather than men.

The Art of Discernment

Recognizing our true intentions is never a child’s play. It requires us to dwell in silence and reflect deeply on our actions and the motivations behind them. In the Catholic tradition, we call this spiritual process discernment; in our Dominican tradition, it is a vital part of contemplation. In modern scientific terms, this is meta-cognition—the act of “thinking about thinking.”

To practice this discernment, we can follow three simple steps:

- Seek the Virtue of Humility The ability to recognize our deepest intentions begins with God’s grace softening our hearts. Without humility, we may never consider that something might be “off” with our actions. Humility empowers us to face the unpolished parts of our humanity with contrition, leading to repentance. It acts as a sensor, detecting hidden motives driven by pride or self-interest.

- Ask Difficult Questions We must be attentive to our emotional reactions. Ask yourself: “When others ignore or fail to appreciate my good deeds, do I feel sad, angry, or disappointed? Do I lose the motivation to continue?” If the answer is yes, the motivation may be self-centered. Another vital question is: “If these good works were taken away from me, would I feel deeply pained or resentful?” Such a reaction often indicates an unhealthy attachment, suggesting we view the work as “ours” rather than “the Lord’s.”

- Request the Purification of Intentions Once we become aware of our interior motivations, we should not be discouraged or stop doing good. Even if our intentions are mingled with selfish desires, God’s grace is constantly working to sanctify us. To purify your heart:

- Be grateful for every opportunity to do good, whether the task is big or small, a success or a failure.

- Redirect praise: When people appreciate your deeds, invite them to thank the Lord with you.

- Embrace criticism: Be thankful for those who criticize you, as they can be instruments of your spiritual purification.

Rome

Valentinus Bayuhadi Ruseno, OP

Guide Questions:

What are our good works we do for our families, our community and the Church? When others ignore or fail to appreciate my good deeds, do I feel sad, angry, or disappointed? Do I lose the motivation to continue? If these good works were taken away from me, would I feel deeply pained or resentful? Do I prioritize our ministries more than my family?